Volume 16, No. 1Drawing and Loss

Issue description

Drawing is typically imagined as an additive, connective and creative process. Adding marks to paper sets up a mimetic lineage connecting object to hand to page to eye, creating a new and lasting image captured on the storage medium of the page.

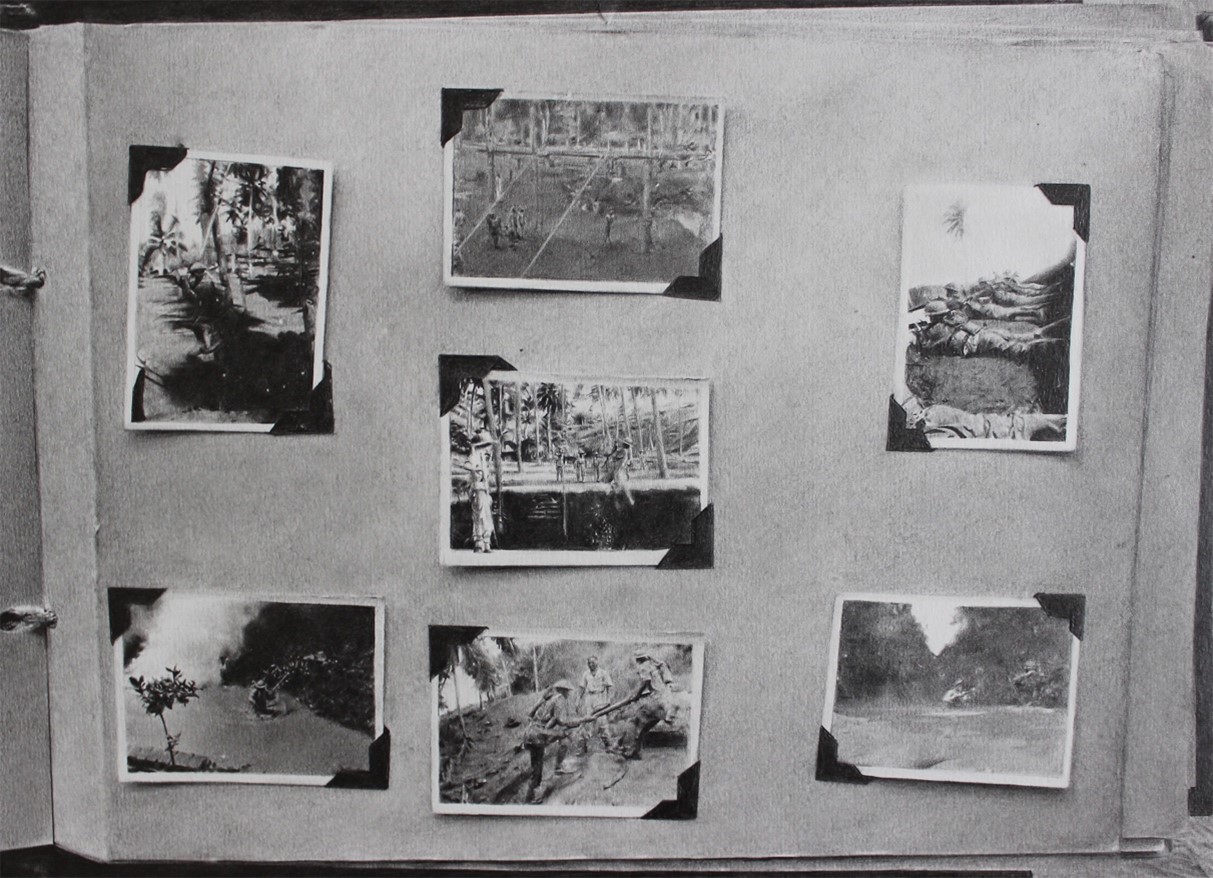

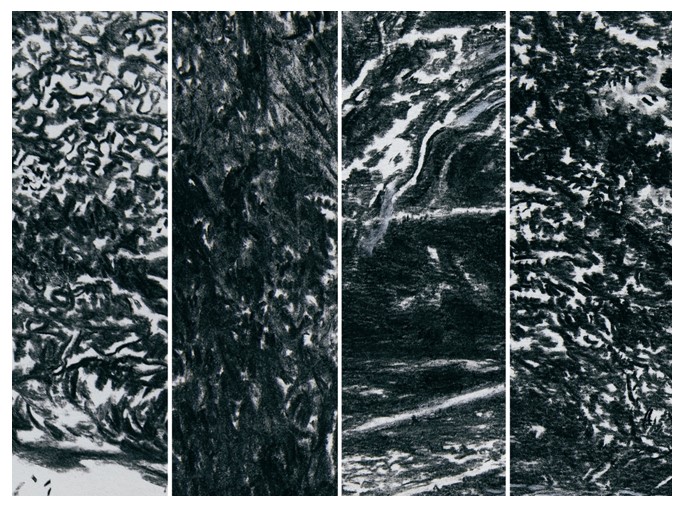

Or does it? A strand of art historical thought from Pliny to Derrida emphasizes what is lost in drawing, exploring the drawing process as a phenomenon that begins from a point of blindness or looking away and proceeds from a perspective of extreme myopia. Implicit in the myopic movement of the stylus is loss of perspective, direction, intention or foresight, such that drawing can be imagined to proceed in a state of not knowing. This changed perspective can result in the conceptual loss or retreat of the thing being drawn, as it is objectified and even dissected—literally or metaphorically—by the person drawing, who might themselves feel alienated from their object by this process. The work of paper conservation shows us that the storage medium of the page is anything but stable, and far from storing an image, can suffer damage and loss of its own without monitoring and periodic intervention in the archive.

This special issue reflects upon the dynamic relationship between drawing and loss, taking a multidisciplinary approach to integrate otherwise heterogeneous connections to this often neglected aspect of drawing.

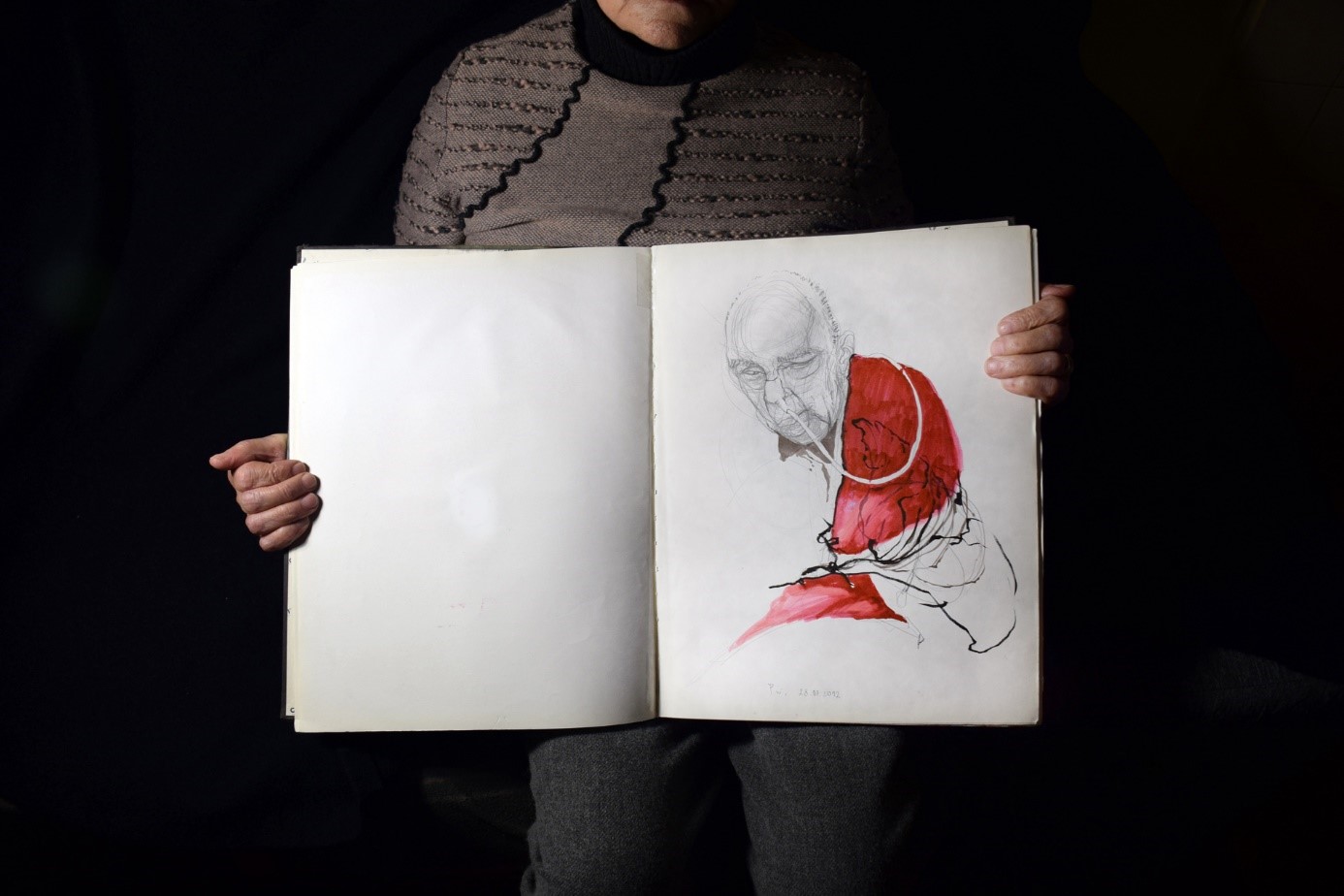

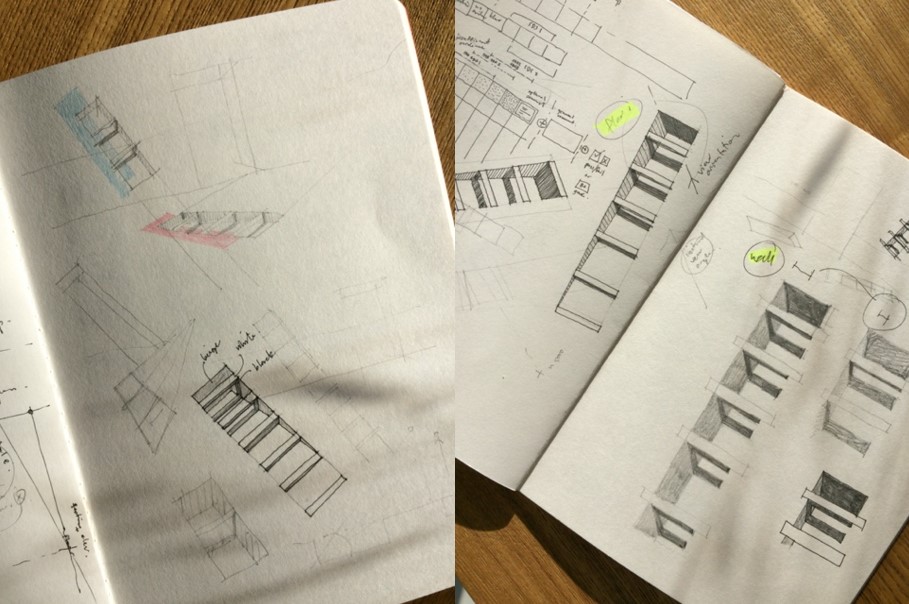

Contributors have arrived at this subject from diverse perspectives, including fine art, philosophy, architecture, the study and personal experience of bereavement and memorialization, the changing climate and political landscapes, and the restrictions of lockdown. Between them they explore a breadth of a theoretical, historical and practice-based approaches to such issues as the losses and gains brought about by the myopic quality of the drawing process; how drawings or drawing processes might mitigate against loss by memorializing, being with, or standing in for the deceased or departed; the haunting or spectral presence of event and line; and the dynamic between the life of the drawing—in process, and once completed—and the life of its object.

This issue was guest edited by Dr Tamarin Norwood, a research fellow at the Drawing Research Group, Loughborough University.

Cover image: Cutting Lines (imprografika workshop-paper show), July 2015, Anthi Kosma