Volume 17, No. 1Drawing Anthropocene

Issue description

This edition proposes an examination of the relationship between drawing – a practice of traces – and the concept of Anthropocene. This is a timely lens through which to examine research engaging drawing in relation to current debates on environmental crisis and invite reflection on the value of drawing in the context of deep time.

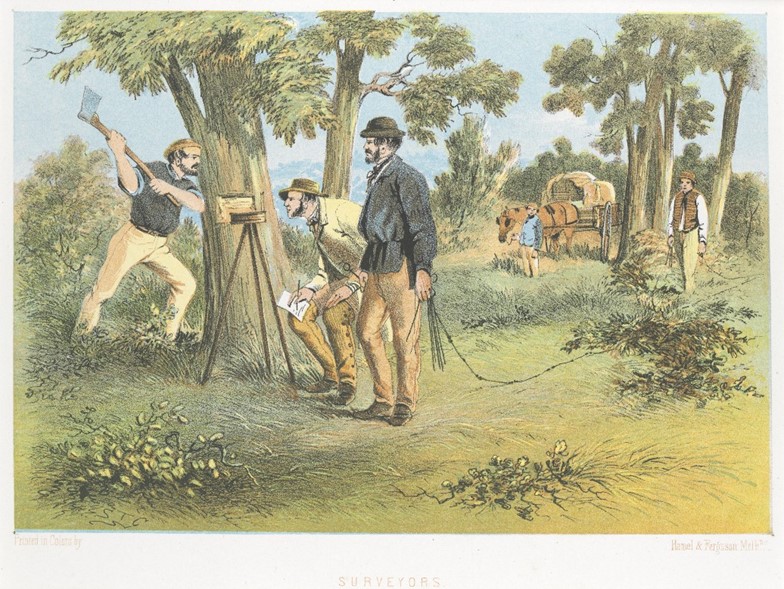

The term Anthropocene, coined at the start of the new millennium by geochemist Paul Crutzen, denotes a new period of geological time, reflecting the extent to which human activity is making its mark on geologic stratigraphy. Essentially, for geologists, the legacy of the Anthropocene will be the traces that our existence will leave in the geologic record in times to come. We might even see this as a collaborative durational drawing spanning the development and demise of human existence!

While there remains debate about the precise starting point of the Anthropocene (and it has yet to be formally acknowledged by the International Committee on Stratigraphy), the concept is now widespread and in common usage as a byword for human impact on the environment. This tension provides a useful provocation, one that prompts questions about how drawing might function in relation to climate crisis and what knowledge it might produce. For example, drawing may examine areas of contention: petrochemicals and carbon release, resource extraction, more than human agency, migrations, or post-human and planetary futures.

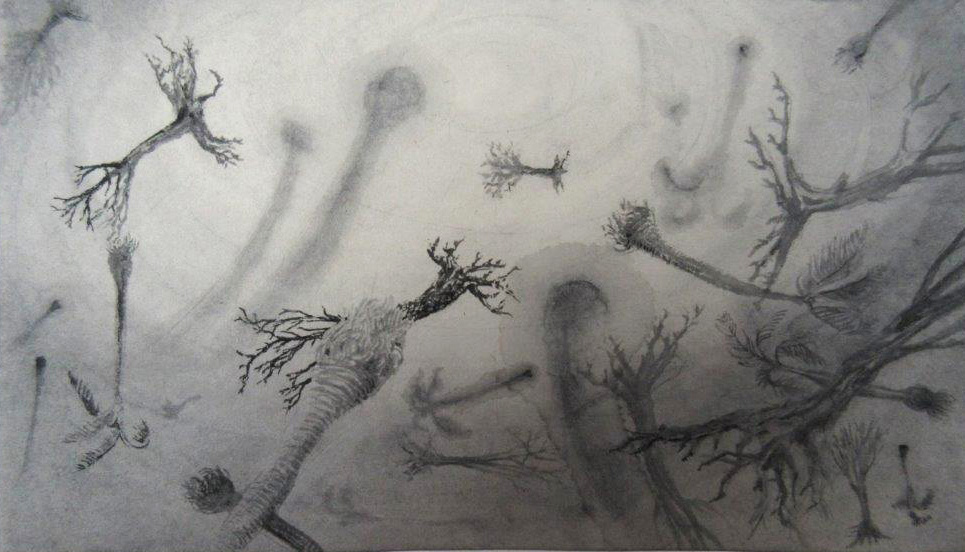

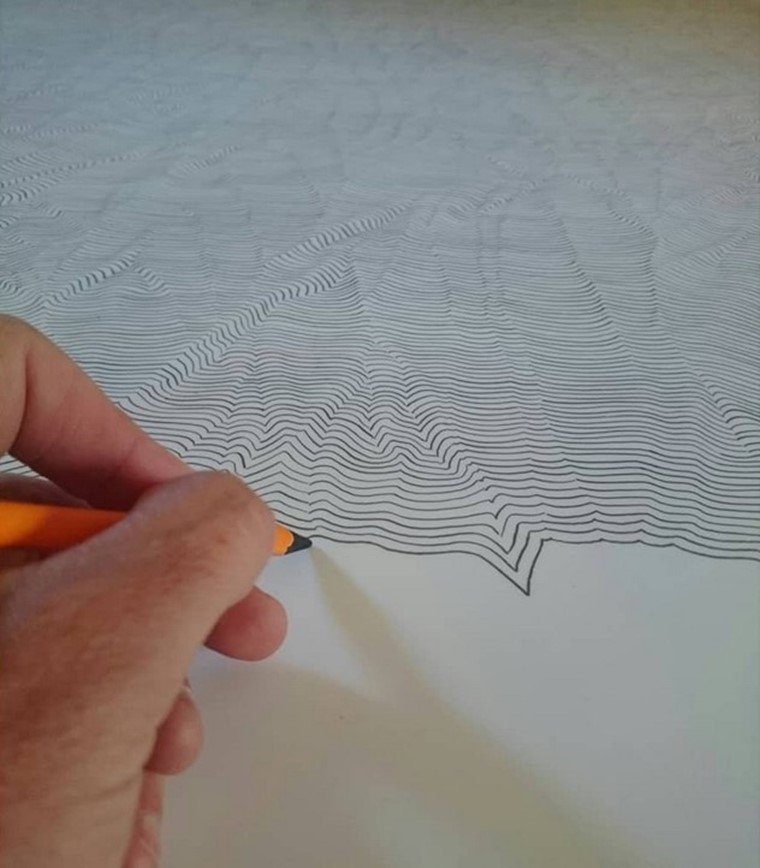

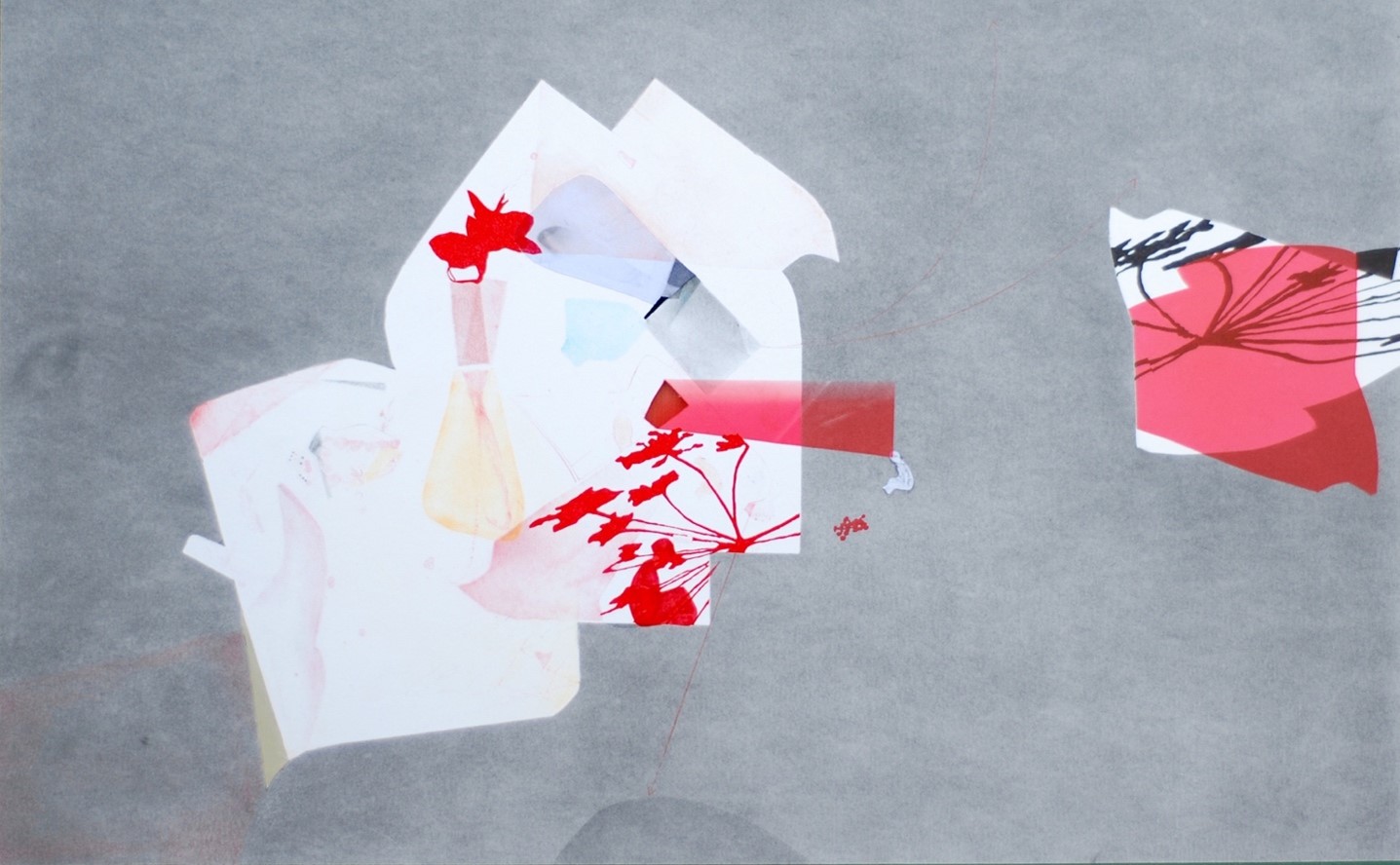

Drawing is an activity of tracing, layering, erasure, the drawn mark often belies the process of its making. It has been called a “trace fossil” (Halperin, 2013). Over the course of the twentieth century tenets of drawing - arguably the trace of an action made over a surface – have been tested, stretched and exploded as artists embraced performance, land art, soundscapes as forms of drawing. Drawing now has many identities, from lines in sand, footprints in the snow, or vapor trails in the sky (Dexter, 2005: 6).

Acknowledging, as many do, that environmental traces - foot prints, tidelines – are a form of drawing, what might this offer for using drawing as a lens through which to enter critical debates on environment? Conversely, how might new thinking emerging from earth sciences and geo humanities reveal new insights into what it means to make a drawing be it conventional or expanded?

Particular areas of interest include, but are not limited to, the following questions:

- How might drawing help us position ourselves in relation to changing ecologies?

- What contemporary or historic strategies does drawing offer for bearing witness to environmental change?

- The Anthropocene reflects changes in global cultures. How can drawing alert us to such changes?

- What does thinking through the lens of deep time offer for understanding drawing and vice versa? Equally, what does this lens of time and change offer to our speculations of futures?

- How might drawing bring us closer to activity in the deep past or timescapes remote from our own lifetimes?

- What geopolitical questions does the concept of Anthropocene raise for ethical practices of drawing? Of how drawing is conducted, who draws, where and for whom?

- How might thinking through the concept of Anthropocene revitalize the traditional field of landscape drawing?

This issue was guest edited by Sarah Casey and Gerry Davies, Lancaster University.